To Idle and to Loaf: A Recipe for “Creative Silence”

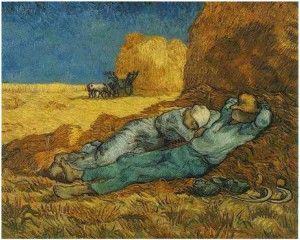

As pointed out this week in an excellent article in Time about van Gogh, Vincent considered himself an idler. In one of his many fascinating letters to his brother, Theo, he clarifies that there are two different types of idlers. About each type, Vincent assures Theo, “You may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.” The first type of idler is just plain lazy.

But the second type of idler, Vincent likens to a bird in a cage who other birds might think is just perched at his ease, but whose heart longs for something elusive in the shape of nest-building and mate-finding, the details of which are vague and fuzzy to the inexperienced and immobilized bird. Van Gogh writes, “In the springtime a bird in a cage knows very well that there’s something he’d be good for; he feels very clearly that there’s something to be done but he can’t do it.” It is clear by the poetic and heartfelt way Vincent describes this second type of “idler,” and the greater amount of time and attention he spends doing so, that he identifies with this type: someone who feels frozen, caged, deeply longing for something just out of reach and all the time judged by the other birds.

But Vincent van Gogh was hardly unproductive. He is one of the most famous and enduring artists, whose work transcends the time and space, even if caged, in which he lived. One who admires his artistic output, his creative genius and ability to realize it on canvas might wonder what his form of “idling” has to do with what he produced. I suggest that Vincent reveals something while describing the “idling” bird in the cage looking out at the world of other birds. As he describes the plight of the caged bird, he reveals some of the way he perceived himself: an observer (looking at all the other birds) and misunderstood…unfairly judged.

That sense of not quite fitting in, not measuring up to every high ideal he had for himself, of not being as successful as the other birds… that uniqueness Vincent felt is deeply human. It is essential to feel those emotions at some point in one’s life if one is to have empathy; and it is that empathetic eye, that closely observing, humble and longing eye that captivate all the eyes that have ever look back at Vincent’s through his art.

So, to summarize: here are two essential components for making great art: some time to observe (idling now and then) and the empathy that is born out now and then feeling like a bird without a flock. Therefore, our boredom and our rejections are in fact gold to mine for art. Good.

Meanwhile, Walt Whitman famously called himself a loafer. So one became a famous artist, the other a famous poet. Is there a connection between down time and greatness? In the opening of “Song of Myself,” Whitman writes:

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.”

This is a far more confident tone than Vincent’s apologetic letter to Theo. In this case, confidence is born of the ease that comes from lounging in the grass. This significantly empty time allows Whitman to sing of himself, and what an epic aria it is. In speaking here of lazing about, Whitman brags. Why? Because he knows that loafing “invites the soul.”

As strange as it seems, sometimes we have to “invite” our souls. We are never without them, and yet it can certainly seem like it after a day of thick traffic, crying children, deadlines and an endless whirlwind of noise filling every empty space: noise from the television, cell phone, constant real and virtual chatter. How often in the course of the day do we allow ourselves to do “nothing” without guilt? Our ancestors went to bed when the sun went down or their candles burned out. But for us, metaphorically and literally, the lights are never off.

Thomas Merton spoke of “Creative Silence.” Published in 1968, this essay illustrates two types of silence: negative silence and creative silence. The first is the type that lets our mind spin every which way with more stream of consciousness craziness than the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses. The latter type of silence, which requires faith, reveals our authenticity through unmasking all the distractions we usually put in place to keep us from facing the fearsome and awesome power of our true selves/souls.

Van Gogh. Whitman. Merton. Three great, very different and undeniably productive people in three different vocations: a painter, a poet and a priest. Clearly, none of them sat around letting the grass grow under their feet forever…though in one case, just long enough to think up the name of a best selling poetry classic.

Next time you berate yourself for idling or loafing, ask yourself what type of idle work you are accomplishing. If the noise is off and the harried mind is still, you just might be doing the most productive “work” you could be: inviting your soul.