Gardening As Prayer

It’s summer, that time of year that naturally lends itself to leaning over rows of basil and zucchini, weeding beds of colorful annuals, and filling vases with bright blooms pruned from hydrangeas. Gardening is the kind of activity that allows the mind to find peace from its constant darting thoughts as the body takes on a prayerful posture, kneeling over herbs and blossoms. It is a meditative and sensory experience to feel one’s fingers in the cool soil even as the hot sun warms one’s arms and shoulders.

As stray grasses and branches are pulled, and branches pruned, one may physically snip away at the elusive, emotional struggles of life: grief, anxiety, fear, anger: projecting them into the shape of nettles and weeds. As the row of beans peek their heads up from the soil, they bring vestiges of green-hued hope. As one clips herbs and vegetables, puts them into a basket and carries it inside to the kitchen, healing and sustenance is carried, too. With our feet firmly planted in the soil, the sun on our backs and the sweat on our brow, gardening is a good time to pray, to braid praise and gratitude and entreaties for help into the roots of our garden.

But on those days the words of a prayer don’t easily come, gardening still offers prayer-as-action: a connection to God’s world and the contribution of one’s humble labor and stewardship to its growth.

A commonly seen garden sign says: “Time began in a garden.” Indeed, every garden bears a trace of Eden: the original perfection in its beauty, the fall in its overgrowth. So too, each garden bears a trace of Gethsemane, where the soil was blessed by tears of blood. Indeed, a garden is a place to go to pray and to prepare the soul for the task at hand.

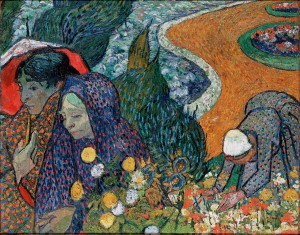

Today’s art is Vincent van Gogh’s “Memory of the Garden at Etten.” It refers to the parsonage garden where van Gogh’s father was assigned. Van Gogh stated that the two women walking together represent his mother and his sister, and also that he wished to portray the way Etten made him feel. Describing the painting in a letter to his sister, Vincent writes, “I don’t know if you’ll understand that one can speak poetry just by arranging colours well, just as one can say comforting things in music. In the same way the bizarre lines, sought out and multiplied, and snaking all over the painting, aren’t intended to render the garden in its vulgar resemblance but draw it for us as if seen in a dream, in character and yet at the same time stranger than the reality.”

The title is reminiscent of the Garden of “Eden,” and to me, so is the scene it portrays. Here is how the painting lives in my imagination: it tells two stories, one happy and one heart-wrenching. The white-capped woman, whose face we don’t see, is hunched over beautiful rows of colorful flowers, which she lovingly tends. This is Eve before the fall, exercising her dominion over all she was entrusted, her hands caressing the garden’s perfection.

The two women on the left, to me, are also Eve. The younger woman, clothed in red, is Eve expelled from Eden, and she walks next to her elder self, the ancient Eve, who wears colors of mourning, but whose dark cloak is tinged with blue, and dotted, starlike, as though foreshadowing Mary, the new Eve. Poignantly, the flowers from the scene of tranquil beauty on the right trespass the cloak of the old woman, uniting her to the garden in memory.

Van Gogh was right: “one can speak poetry just by arranging colours well” and it can be drawn as though a dream. The space of a dream is the language of archetype and myth, and my imagination enters Vincent’s painting as I dream of the Three Eves. In my poem, “Rondeau for Sarah’s Garden,” I paint a garden with words, imagining Abraham’s Sarah planting “to bless her body’s final home,” and thus, comforting her old age.

Gardens are beautiful, prayerful, meditative places and under all those layers of roots and soil are artifacts and archetypes just waiting for our hands, spades and imaginations.